-

-

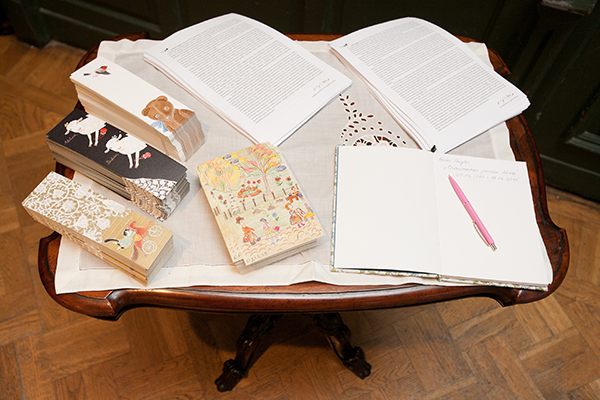

The Wonderful Garden of Dreams exhibition by Anita Paegle, one of the most prominent Latvian children’s book illustrators, is on view from 25 March until 18 April 2015 at the Latvian Academy of Art. Author of many drawings for magazines and designer of greeting cards, postage stamps and coins, Anita Paegle is nevertheless best known for her illustrations to thirty-two children’s books. Art critic Andris Teikmanis speaks with Anita Paegle about illustrations, text, art imagery and the wonder of creation.

-

Andris Teikmanis: An artist’s journey to his or her unique visual language is

not an easy one. What was it that determined your choice in favour of book illustration? At which point was it that you realised that is was the road you were meant to take?Anita Paegle: As a child, I loved to browse through books; initially it was just browsing, and the thicker the book, the better it seemed to me. Books were quite thick in those days but there were very few pictures in them. I turned the pages, looking for the beautiful pictures – and found them. The colouring-in stage followed.

AT: Book improvement?

AP: Yes. I felt that they should actually be more beautiful. If there was a cherry in a black-and-white illustration, I absolutely had to colour it pink or red. Then I started to draw my own little books. By the age of 6, I had made a number

of my own little books, sewn together by Mum. Later, at school, I was not thinking about books at all – until I was given the task of illustrating a fairytale. That was beautiful. It was in the eighth grade of the Rozentāls Art School that I made a conscious decision to switch from oil painting to watercolours. It was a technique that suited what I could do and wanted to do most of all. It was at this point that I was first asked to make some book illustrations.AT: When did the images appear that made you realise that they were yours? Was it at Rozentāls School or during your studies at the Academy of Art?

AP: The images came earlier, during my first years at school. I forgot them later; they were lost for so many years. I was looking for them – and then I found them.

AT: It must be a feeling of happiness and fulfilment. Normally people struggle to remember even tiny fragments of their childhood – but recapturing the feeling you had drawing pictures as a child, that must have been a very special spiritual adventure.

AP: That is true – that really describes it. The thing is, you draw pictures, you check the composition – everything seems to be in order, and yet there is something missing. Your exhibition features works that have been started and have not been completed. You haven’t found the feeling that is necessary to complete them. You carry on the search: you make another picture, and another – until you find a little detail that solves everything and you can finish the work.

AT: The relationship between a text and an image is complex. How are the images born? What serves as the first source of inspiration?

AP: When I read the text, I almost draw it in pictures in my mind. I visualise images and then I start looking for them in real life; I also look for the places I have imagined. I look for people whom I want to use to draw my characters – because I like my characters to have the faces of familiar people and I like that fact that everything is for real. As I read the text, I see the composition of the work; then I start looking for the right place, for all sorts of details.

AT: So you draw a mental picture in your mind, and then you have to make it real?

AP: Exactly. Sometimes you read a fairytale or a poem, and these moments are wonderful. As you are looking through a window, your hand is drawing, and this feeling, this sense of composition is incredible. Then several months are spent looking for details, angles and locations. It took three minutes for the idea to be born but then it takes three months to make it real.AT: The reader reads the text and looks at the illustrations only in the context of the text. But if we see the whole body of illustrations, for instance, at an exhibition, we see that it is actually a very special world. The world of different fairytale and poetry illustrations is united by a set of laws and a logic of its own; it is a fantastic parallel world alongside ours. Which is the moment when the text creates the images of this fantastic world?

AP: Images are created by the text at once. They are easy to find. The book as a whole is a different matter. When you are making it, you have to make sure that the illustrations are ruled by harmony – by wondrous serendipity and harmony at the same time. It is particularly important when you are making illustrations to a collection of poems: you have to think about all the poems at once.

If the book were not for real – if it did not need to be finished and published,

I could go on drawing forever. Because there are poems that – I would even say – confront you later and shout in your face that they haven’t been drawn.

I cannot say why it is that they haven’t been illustrated; as likely as not, they haven’t been simply forgotten. They have been left alone in the hope that someday I might be lucky enough to meet them again. The images seem to be waiting for me to choose them – or sometimes they are choosing me.

The road to the one and only image is so fascinating. So many sketches, so many pieces of paper covered in drawings – and then a line in a corner. It is a bit distant from the other lines, and next to it there is a little face that goes on to become the central character of the book.

Besides, you have to stick to a different composition, a different harmony of images in a book. The reader is turning the pages, and it is happening fast.

The images have to adjust to that.AT: So that means that illustrations have their own narrative, independent from the storyline that has to be related to the reader?

AP: Yes. Sometimes you want to draw something but there is not enough space in the book for that. And then it almost feels as if the characters do not understand why there is not enough room for them, and they are left outside, feeling sad.AT: Maybe you should consider making a book featuring the characters that are left over? What sort of characters are left outside most often – people, animals

or birds?

AP: It used to be birds and animals. It’s just that I generally tend to draw more birds and animals because we are surrounded by people all time while the small creatures remain invisible in the everyday life.AT: What are your favourite characters or images?

AP: I love drawing houses.AT: Houses?

AP: Yes, houses. They keep so many secrets. They have windows and doors. Behind each window, there is a story that can be told by the people who live there. I also often think that anything can happen to a house. I can stand on

a corner of a street and draw buildings, observing the way they look and how they keep changing every year.AT: In the world of your pictures there is no strong lights and shades, no play of coincidences. It is a world of ideas, an ethical world. What do you do when you have to depict a negative character, an evil fairytale creature?

AP: There are not very many evil characters in my pictures; besides, they are not completely evil – they will surely change for the better. But I did find it quite hard to draw evil characters. I used to draw them sad, later – angry.

I could draw mysterious characters, not the really evil ones, no.AT: What is the reaction of the other half to your pictures? The authors of the

text – writers, poets? What is their opinion of your world? You are, after all, creating another world that exists alongside the text, and it features many details that are absent in the text.

AP: Writers typically make very few comments on these details because, during the actual process, they do not see the pictures that are being made for their work. Sometimes I have felt that it would be nice to discuss my work with the author of the text – these are two completely different worlds after all.

I had this sort of collaboration with Jānis Baltvilks. It was important for me to hear Jānis’ opinion, and he said that he liked everything that I was doing. That was inspiring and assuring. Jānis wrote books about nature. I learnt a lot about birds and plants when I was working with him. Jānis asked me if I liked crows.

I said that I found smaller birds with tiny beaks and tiny wings more appealing. He was disappointed and said that the crow is a very clever bird; he told me

a lot about the life of crows. Then I started drawing crows. That was a pure coincidence – they seemed to crop up in one poem after another. Now I also feed crows in the park and have even become friends with one of them –

with a very fluffy, beautiful and clever crow.AT: Which is the text that appeals to you most? How do you go about getting

a feel of a text?

AP: It has been quite some time since I last made some illustrations to poems. There is a much slower rhythm to a fairytale. A poem describes events in

just a few lines, so you have to find the image very quickly. Also, there can sometimes be all sorts of little jokes and bits of nonsense in children’s poetry. Sometimes, when you read a good poem, you don’t want to do anything

at all. You could simply read and enjoy it, and yet you have to depict it as

well. Or sometimes you read a poem and you think that everything is pretty straightforward in it – but then you make a picture and it just does not fit the poem. Not the right harmony. You can make up the composition but you need details as well. Speaking of poetry, I love the dark poems – the ones featuring a rhythm, a change of night and day.AT: The dark poems? Does it mean that you read poetry and see it colours?

How does the rhythm of words or the structure of a poem create associations with colours?

AP: It can also be the event described in the poem. For instance, it could be

a nocturnal poem, a real nocturnal poem – or it could describe the moment when the nightfall is approaching. I used to think that drawing daytime was not so interesting. The nocturnal world seemed so much more wonderful because people sleep at night and they do not see the miracles that take place at night.AT: Do you also create a story when you are making illustrations?

AP: You create your own story in the illustrations. You find your story and you can add to it in your mind. And then you think that children will be looking at the picture and everybody will see something in it. You create your own story, and that is indeed a wonderful sense of happiness.AT: Do you see your viewer as you make the illustration? Is it children?

Children’s parents? The writers? You as a child?

AP: Yes, you could say that I – as a child and also today – am definitely one of the viewers. But I would still love everybody who looks at my illustrations to find something of his own in them. It would be memories to someone and fragments of their dreams to someone else. The most interesting thing is meeting children at schools and showing them my illustrations, and then some of them would notice things I had thought no-one else knew about. Children are very keen observers; the questions they ask show that they have discovered my secret.AT: So it means that sometimes you hide a secret message in your illustrations?

AP: Exactly, a secret one. If someone finds it, it is like a prize for the observant viewer.AT: Do you reveal to the children that they have discovered a secret?

AP: Yes, usually I tell them. And I also ask – how did you notice that?

AT: Since Renaissance, artists have been depicting themselves somewhere inside their world. Are there any images of yourself hidden in your art?

AP: Yes, it is quite possible that the silent observer hiding behind a blade of grass is me. Or the girl sitting on the poppy stem. I spent the summers of my childhood in a meadow among poppies. I was wondering then – what would it be like to sit on a poppy stem? And then I went on to experience it for real in my art. the artist is always inside his or her art; it is like looking at yourself from a wonder mirror.AT: Which is the moment when you experience the miracle of creation? Is it when the work is finished or when the first image is born?

AP: The sense of miracle has to be present all the time. It has to be there when you start a piece and when you work on it. The actual work on the illustrations can last for many endless months, but when it is finished, you have to have this feeling of miracle. That is the way to make sure that the work is a success. There has to be this feeling of miracle; if there is, then you know that you have done well.Dr., Art critic Andris Teikmanis,

The Art Academy of Latvia

Anita Paegle (C)

Built with Berta.me