-

-

Little Sheep and Ponies

By Anete Piņķe, Satori.

-

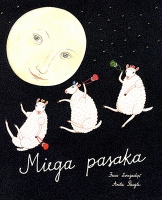

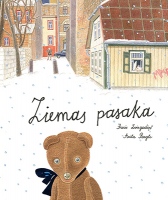

About ‘Winter Fairytale’ and ‘Sleep Fairytale’ by Juris Zvirgzdiņš and Anita Paegle. The Zvaigzne ABC publishing house, 2014.

‘Look at these cute little sheep!’

‘No, you better take a look at this, Mummy! What cute ponies!’

That is an approximate account of the dialogue between me and my four year-old daughter in a bookstore, in front of the children’s literature shelf. I was admiring the cover of the latest fairytale by Juris Zvirgzdiņš, featuring curly sheep floating in black nocturnal skies, while my daughter was gushing about a marshmallow-coloured calendar from My Little Pony series. Our tastes regularly clash. ‘Mummy, why can’t I have the pink t-shirt with the little princess?’ Marija is whining while I drag her through the cunningly placed display of children’s goods on our way to the supermarket refrigerator with dairy products. ‘Why can’t I have the Barbie magazines and the hat with Hello Kitty? Why can’t I have the ponies?’

It is not really that she can’t. But I have difficulty coming up with an argument that I could use in these daily confrontations: I am not at all sure that I have the right to decide what my daughter should find beautiful. I was taught as a child that ‘tastes differ’ and you have to respect other people’s aesthetic sensibilities but at the same time – I was also told that certain things just do not make the grade of sophisticated good taste. And so the boring greyish-beige ‘good taste’ cast its gloomy shadow over the most lovely things in the world: the plush carpet with little deer at the Kauguri department store and ‘banana clips’ – baby blue, pink and yellow plastic hair grips temptingly displayed in the window of the railway station press stall. ‘Why do you like the ponies, not the sheep?’ – ‘Because they are such lovely colours and they smile so nicely.’When the sheep on the cover of the ‘Sleep Fairytale’, accompanied by the moon from ‘Winter Fairytale’ (they are sold as a set), end up in our home,

my daughter caresses the velvety covers, touches the silky blue ribbon that adorns the teddy-bear’s neck and echoes me: ‘Very pretty!’ And yet I know that the most beautiful book on her shelf is ‘Hello Kitty: My Day’. Her favourite colour is pink, just like Kitty’s. Kitty lives in a room with pink curtains on the windows; every morning, she exercises and feeds her goldfish. It is nothing like the strange fairytale about Reinis the teddy-bear who lives in a Riga slum with a cat and a play ball and tries to get rid of drunken tramps. Because this is a short summary of the ‘Winter Fairytale’ story.Zvirgzdiņš’ fairytales are so far from the synthetic world of the consumerist society that they unwittingly become its critique. He defends genuine childhood like a knight with a toy sword. Seemingly aware of it, the writer references ‘Home Alone’, the Hollywood thriller-fairytale of the 1990s, in

his ‘Sleep Fairytale’ – except there is nothing breaking and crashing in the nocturnal adventures created by Zvirgzdiņš. Well, perhaps there is a slight crunch of spilt sugar underfoot (an accident during a pancake fry). A slow rhythm and sentences that seem a bit too long. Sometimes they are as slow as time in the bygone days when mums did laundry by hand, made clothes, yet always managed to get everything done.In Zvirgzdiņš’ fairytales, some old and long-forgotten flavours float in the air

with snowflakes and pancake flour: condensed milk, onion garlands and dried apple slices, pancakes with cinnamon and ice-cream. There is the sound of an abandoned old VEF radio; an old wicker chair is slowly disintegrating. I have

to explain my daughter what a wooden toy sword is – and a half-blue half-red play ball can only be found in an antiques shop today. The characters of the book hail from the pantheon of Zvirgzdiņš’ mythology, hence they are already familiar to us: a boy; cats; teddy-bears. (It is a noteworthy fact that teddy-bears first appeared as late as in the early 1900s; they were to the Western children of the time as ‘Hello Kitty’ is to ours today.)Here, too, Zvirgzdiņš has stayed true to his mission of an educator and

deftly worked in the figure of the Latvian poet Aleksandrs Čaks in his Winter Fairytale. The episode in which the cat and the bear mistake the snow- covered dome of the poet’s monument for a ball is by far one of the loveliest moments in the book. And I am pretty sure now that my daughter will recognise Čaks, just like she has been reciting ‘the River Daugava; the library; the Castle; the Zaķusala TV Tower’ while crossing a bridge ever since I wrote a review of Zvirgzdiņš’‘Ahoi! Flood in the Daugava’.

Admittedly, the fairytales are somewhat lacking in intensity of action; likewise, the composition could have been more balanced – for instance,

the ‘Sleep Fairytale’ seems to be cut in two. Furthermore, I also found the criticism of the grownup’s world – all the going on about Dad’s BORING and STUPID films – somewhat tendentious. The somewhat incomprehensible excessive use of CAPITAL LETTERS seems to demand from the reader the

use a funny accent, like the one in old spoken text recordings – with pauses and fancy emphases. In ‘Sleep Fairytale’, capital letters are dominating the text to such an extent that instinct tells you to pay special attention to the words that are written in keeping with traditional grammar rules. And yet – all is forgotten as soon as the counted sheep climb through the window in alphabetical order: Adelaide, Beatrice, Cecilia, Dace, Elsa, Fanny, Gertrude, Hermine, Justine, et al., each coyly fiddling with a purse that carries the first letter of her name.

Both books have been illustrated and designed by artist Anita Paegle. Each snowflake has been painstakingly shaded, and you could count every hair of the bear’s fur. Her pictures wade into the letters and softly add their voices to the story, sometimes taking over and becoming the dominant narrators. The silky pages of Galerie Art Silk paper have been transformed into a dark night behind the window of a cosy room and a white silence in a snow-covered Riga. And it is only upon re-reading the fairytale that you discover that it

is actually the pictures where you find the smell of the squeaking snow

and the graceful movements of the sheep, not the text of the fairytale. Last winter these illustrations went on view in picture frames at the Auditorium of the Latvian Academy of Art; the artist won the LAA Annual Award for them. Throughout the years, having created the illustrations to almost 30 children’s books, Paegle has remained true to her unique style. I first saw her pictures as a reader of the Zīlīte children’s magazine, but it is only today, as a mother, that I can fully appreciate this refined beauty.

Our most precious moments are often also literally beautiful. Quite

recently, Marija’s grandfather told me about a pair of footwear made by

his father, a shoe-maker living and working in the times of the first Latvian independence – burgundy ladies’ shoes on a small heel, with suede straps and little buttons covered with the same material. This piece of beauty hadbeen locked in the child’s memory and preserved for lifetime. Or let’s take my mum who often remembers the doll with a porcelain face and a pink flower-patterned cardigan, allegedly brought to the house and placed under the dining-room table by the Easter bunny. In our most precious memories, teddy-bears dance with plush deer from a carpet – and they will be joined by pink ponies someday. The most beautiful things of one’s childhood end up in fairytale books – so beautiful that grownups want to read them yo their children at bedtime.

While writing the two fairytales, Juris Zvirgzdiņš has been recalling with great pleasure the flavours and aromas of the loveliest moments of his

early life. As stylish as during his hippy years when the up-and-coming poet sipped his double coffee at the Kaza café, the It bohemian hang-out of the time, today Zvirgzdiņš, an aristocrat of the childhood world, celebrates THE FESTIVAL OF EATING and builds snow pyramids in the company of bears

and presidents (‘Winter Fairytale’ also contains a mention of the current President, albeit a brief one). Pancakes with sardines; tramps that are scared by the hooting of an owl and become Fathers Christmas and a wolf defeated by a toy bear with two toothbrushes. One-two-three-excuse-me. A genuine example of hippyish-hipsterish nerddom in modern-day Latvia, Riga, the neighbourhood of Ziedoņdārzs.

Anita Paegle (C)

Built with Berta.me